Following the severity of the situation with fine particulate matter, or PM 2.5, that blanketed the entire upper northern region of Thailand from February to May 2019, there has been a significant impact on the health of the population in that area. Clear evidence confirms that PM 2.5 can accumulate in the alveoli of the lungs and permeate into the bloodstream, spreading throughout the body. It has become the fifth leading cause of death worldwide in 2015 (Cohen, 2017). Additionally, the World Health Organization reported that in 2016, air pollution caused 7 million deaths globally, with 4.2 million due to outdoor air pollution (Ambient Air), 91% of which occurred in countries in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific (WHO, 2018a). In Thailand, the latest reports show the number of patients affected by the smog issue, monitored through epidemiological groups and urban disease control groups. The Department of Disease Control in Chiang Mai reported on their website that from health impact surveillance of smog conditions in Health Area 1 between 10th and 16th February 2019, 8 northern provinces of Thailand, including Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Phayao, Phrae, Mae Hong Son, Lampang, Nan, and Lamphun, reported a total of 26,614 cases in 4 disease groups, equivalent to an illness rate of 707.28 per 100,000 population. The highest reported diseases were all types of respiratory diseases, followed by all types of heart and vascular diseases, inflammatory skin diseases, and eye inflammation, with illness rates of 360.18, 295.25, 27.35, and 24.50 per 100,000 population, respectively. The most at-risk groups are children and the elderly.

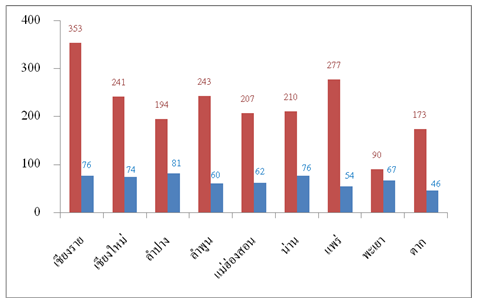

From the PM 2.5 situation report of the upper northern region of Thailand by the Pollution Control Department for the year 2019, it was found that the highest PM2.5 levels were in the provinces of Chiang Rai, Phrae, and Lamphun. Meanwhile, the provinces with the highest number of days with PM2.5 levels exceeding the standard were Lampang, Chiang Rai, Nan, and Chiang Mai.

However, the significant causes of the smog or particulate matter in the upper northern region of Thailand are forest fires, open burning, vehicle emissions (Mongkol, 2010), and industrial pollution. Jiamjai Kreuasuwansri and colleagues (2008, cited in Mongkol, 2010) found that 50 – 70 percent of the fine particulate matter originates from forest fires and agricultural burning, and approximately 10 percent from diesel engines, with the remainder being dust carried from other sources.

However, from the study by Nior and Sarawut (2012), it was found that the main cause of the smog problem is the burning behavior of the agricultural sector, which includes burning in forested areas. This aligns with the findings of Suttinee Dantri and colleagues (2011), who also identified dust carried from other sources. Additionally, some areas are affected by air pollution resulting from forest fires in neighboring countries (Manomaiphiboon, 2007; Leelasakultum, 2009).

Monitoring of fires, also known as "Hotspots," has been developed since 1998 by AVHRR (Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer) (Justice et al, 1998). However, this system has been continually improved under the stewardship of NASA. Currently, there is a developed system for monitoring burning areas and hotspots via satellite in the MODIS system (The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), which captures images in multiple spectral bands (Justice et al., 2002; Giglio et al., 2003). This involves creating mathematical conditions for the infrared wavelength by comparing the brightness of an image point with its surroundings (Giglio, Descloitres, Justice & Kaufman, 2003). The MODIS satellite detection system displays hotspots with a pixel size of 1 kilometer, with a confidence level ranging from 0% to 100% (Giglio et al., 2003). The hotspots are categorized into three major groups: low confidence (less than 30% confidence), moderate confidence (30% – 80% confidence), and high confidence (more than 80% confidence). Selecting high-confidence hotspots helps reduce various potential errors (Giglio, Kendall and Tucker 2010). Currently, MODIS satellite hotspots are applied globally to monitor fires, and a comparison between the hotspot locations shown in satellite imagery and actual ground locations shows that they usually correspond accurately.

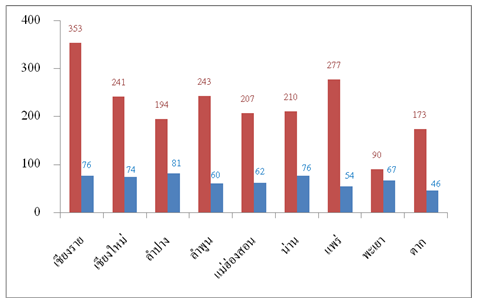

Figure 1

Average 24-hour values of maximum PM2.5 and the number of days exceeding the PM2.5 standard per province

Red represents the 24-hour average of PM2.5 values, and blue represents the number of days exceeding the PM2.5 standard per province

Source: Adapted from the report of the Pollution Control Department, 2019

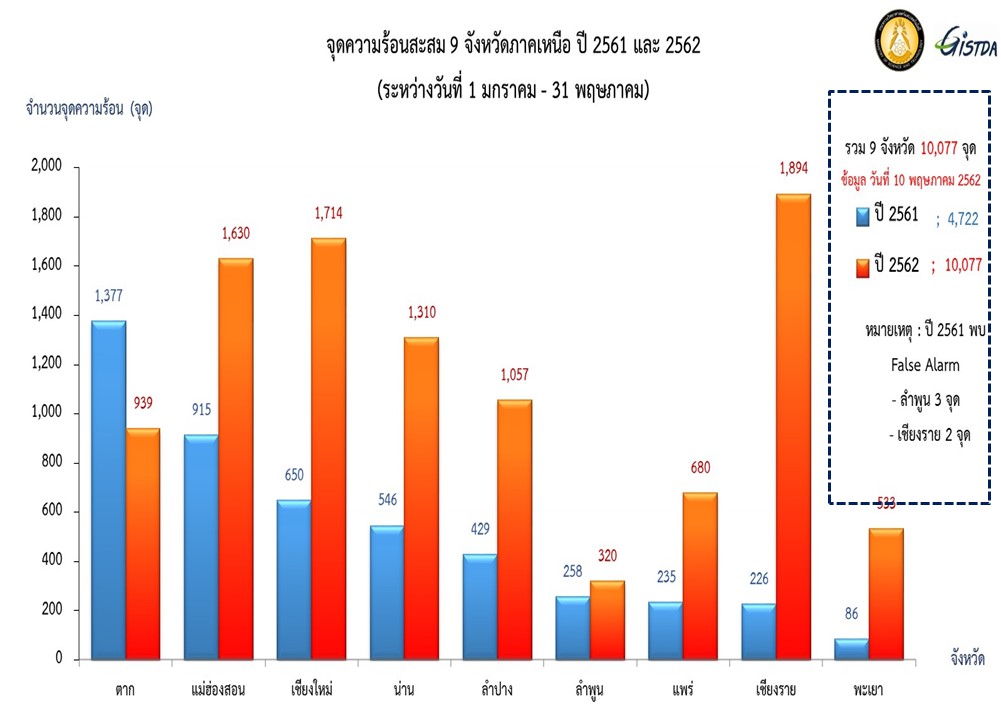

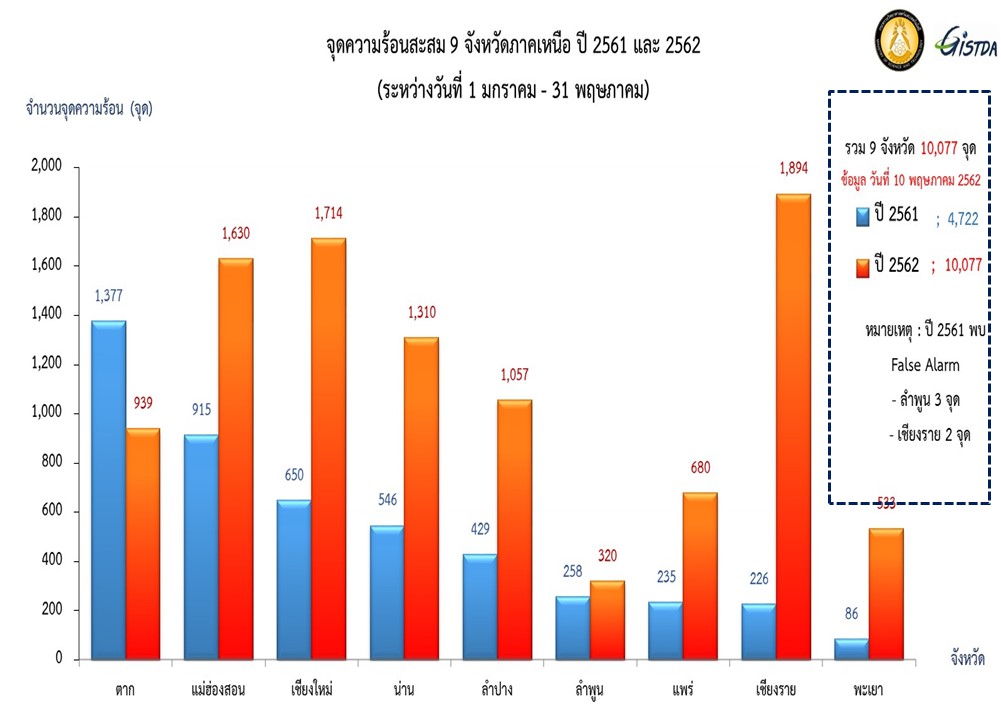

Figure 2

Statistics of Hotspots for the year 2019 and Hotspots in 9 provinces of the Northern region

Source: Office of Space Technology and Geographic Information Development (Public Organization), 2019

The hotspot situation from the Office of Space Technology and Geographic Information Development (Public Organization) for the year 2019 shows the severity of the burning situation increasing in all areas of the northern part of Thailand, especially in the provinces of Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, and Mae Hong Son (Figure 2). The impact of forest fires and smog has significantly affected the health of the population in the area, as evident from the number of patients affected by smog in the northern region since 2007. On average, about 100,000 cases per day, particularly among children, the elderly, and those with respiratory conditions. According to a report by the Department of Disease Control on March 10th, 2007, to March 22nd, 2007, there were 57,765 cases in hospitals in 9 provinces, including Chiang Mai, Lamphun, Lampang, Mae Hong Son, Phayao, Chiang Rai, Phrae, Nan, and Kanchanaburi, averaging 7,220 cases per day, over 90% of which were general respiratory diseases with non-severe symptoms. The highest number of patients was in Chiang Rai with 18,412 cases, followed by Lamphun with 13,936 cases, and Chiang Mai with 8,399 cases (Office for the Development of Health Information Systems, 2007). This corresponds with the report from Chiang Rai Prachanukroh Hospital, the main hospital in Chiang Rai province, which reported an unprecedented number of patients seeking treatment since March 2007, averaging 2,200 people per day (Office for the Development of Health Information Systems, 2007). Most patients treated were affected by the smog conditions covering the entire province, with symptoms primarily related to respiratory issues and eye irritation. The smog situation has increasingly impacted the health of the public, as seen from the number of patients affected by smog in the northern region in 2019, with nearly 20,000 cases per day on average. However, the areas that need the most monitoring are those with the most burning, namely Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, and Chiang Rai provinces (Office of Space Technology and Geographic Information Development (Public Organization), 2019).

Currently, the Cabinet has resolved to make "the resolution of particulate matter pollution" a national agenda. It has approved an action plan to drive this national agenda for "solving particulate matter pollution" to provide guidelines for addressing the overall particulate matter problem in the country, especially in crisis areas, by integrating operations in all sectors (Pollution Control Department, 2019). Therefore, to cope with the crisis situation of particulate matter levels exceeding standards that impact the health of people in the area, especially vulnerable groups like children living in areas with significant burning, the body is regularly exposed to the toxic particulate matter from open burning, leading to the accumulation of toxins in the body that can impact long-term health. This led to the initiation of the "Project on Creating Learning and Communication to Combat Dust Hazards for Health Protection in Schools during the Particulate Matter Crisis" in three pilot areas: Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong Son provinces. These three provinces are considered critical areas with the highest risk of particulate matter problems exceeding the standard, having the highest number of hotspots in the upper northern region of Thailand and posing a significant health risk to people in the area, particularly school children. The project is focused on daily real-time air quality monitoring in schools, enabling them to know the level of dust in the school and to design suitable learning activities accordingly, such as suspending outdoor activities, adapting physical education classes to indoor settings, declaring student safe zones, and designing learning about dust hazards in schools to help students understand the crisis situation and protect themselves safely, including the normalizing of wearing face masks. This approach effectively reduces health impacts. Concurrently, students can pass on the knowledge to their families to safely cope with the dust crisis. This project emphasizes creating mechanisms in schools to deal with dust problems, fostering community and local cooperation, with schools as the core for creating knowledge and various activities. The students are central to this, with linkages to the community through cooperation with local government organizations, by establishing tangible community policies on handling dust crises through local ordinances and ultimately presenting these policies at the national level.

This project integrates cooperation from multiple sectors in the area to study and create model spaces for dealing with critical particulate matter levels in schools. It explores the feasibility of creating learning activities about dust and health for upper primary education (grades 4 to 6) and the possibility of proposing tangible policies on dust and education. The integration involves various entities, including a limited partnership, Temtem Social Enterprise, in collaboration with the White Giant Association, which will support the provision of fine dust measuring devices. The Provincial Education Offices of the three provinces are involved in selecting pilot schools in high-risk areas, ten schools per area, totaling thirty schools. Local government organizations, Plan International Thailand, The North (Northern Degree), Chambers of Commerce, Industrial Councils in the area, and provincial disaster prevention and mitigation are all part of this initiative, aiming to create model spaces in schools to handle dust in crisis areas and propose policies on dust and education.

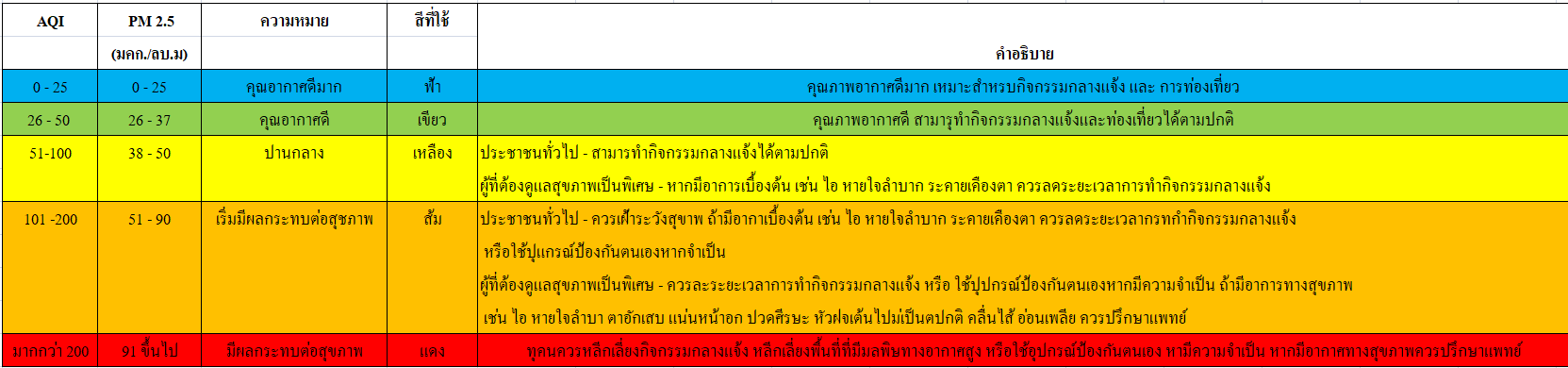

This project also involves creating learning activities about dust and its hazards through designing knowledge sets that can be practically used in schools, based on real experiences of facing particulate matter exceeding the standard, and communicating through a "Health Flag" system. This system uses flag colors to indicate PM 2.5 levels impacting health according to the standards of the Pollution Control Department (Figure 3). It aims to enhance health safety for students in areas, enabling them to adapt and create self-reliant communities in times of fine particulate matter crises affecting their health. Moreover, it promotes practical learning and shared learning spaces in communicating dust levels to the public, by enhancing the communication skills of teachers in high-risk and surrounding areas, in collaboration with experienced communicators such as The North. This approach helps in understanding the particulate matter situation in the area and jointly caring for the health of the community. Additionally, the initiative includes studying policies for dealing with dust in crisis situations in educational institutions. All these actions are part of one of the three measures driving this national agenda (Pollution Control Department, 2019).